While scanning through the news recently for the latest updates from the World Health Organization (WHO), I was inundated with information on health drives, influenza breakouts, vaccination programs, and pandemic agreements. But what caught my eye was a factsheet in the newsroom that pointed at the increasing contribution of non-communicable diseases to the mortality rates in most countries , except the very poor.

About 7 out of 10 people die globally out of cancer, cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, pulmonary diseases, liver/kidney failures, or diabetes. Deaths due to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias have overtaken to become the second leading cause in high-income countries.

This is counterintuitive, because living in a golden age of scientific technological advances, human civilization should have attained its pinnacle by now. Yet statistics reveal a different story. They tell us that the right to health of millions is increasingly coming under threat due to diseases and disasters, conflicts, hunger, climate crisis, and pollution, devastating lives and putting people in increased psychological distress. But why?

As WHO puts it, it is important to understand why people die the way they do, to improve how people live. Among the key messages they have put forth, the one that struck the chord with me is “to know the health needs of the populations and act on them”, which further highlights the need to gather and analyze data, disaggregated by race and ethnicity, place of residence, age, gender, education level, and economic status.

This is what we at the Center for Equitable and Personalized Health (CEPH) have been rooting for -- contextualisation of non-communicable disease data for people of Indian-origin to enhance preventive & personalized healthcare for them, elucidating their disease susceptibility, and reducing therapeutic failures. This is by no means a small feat.

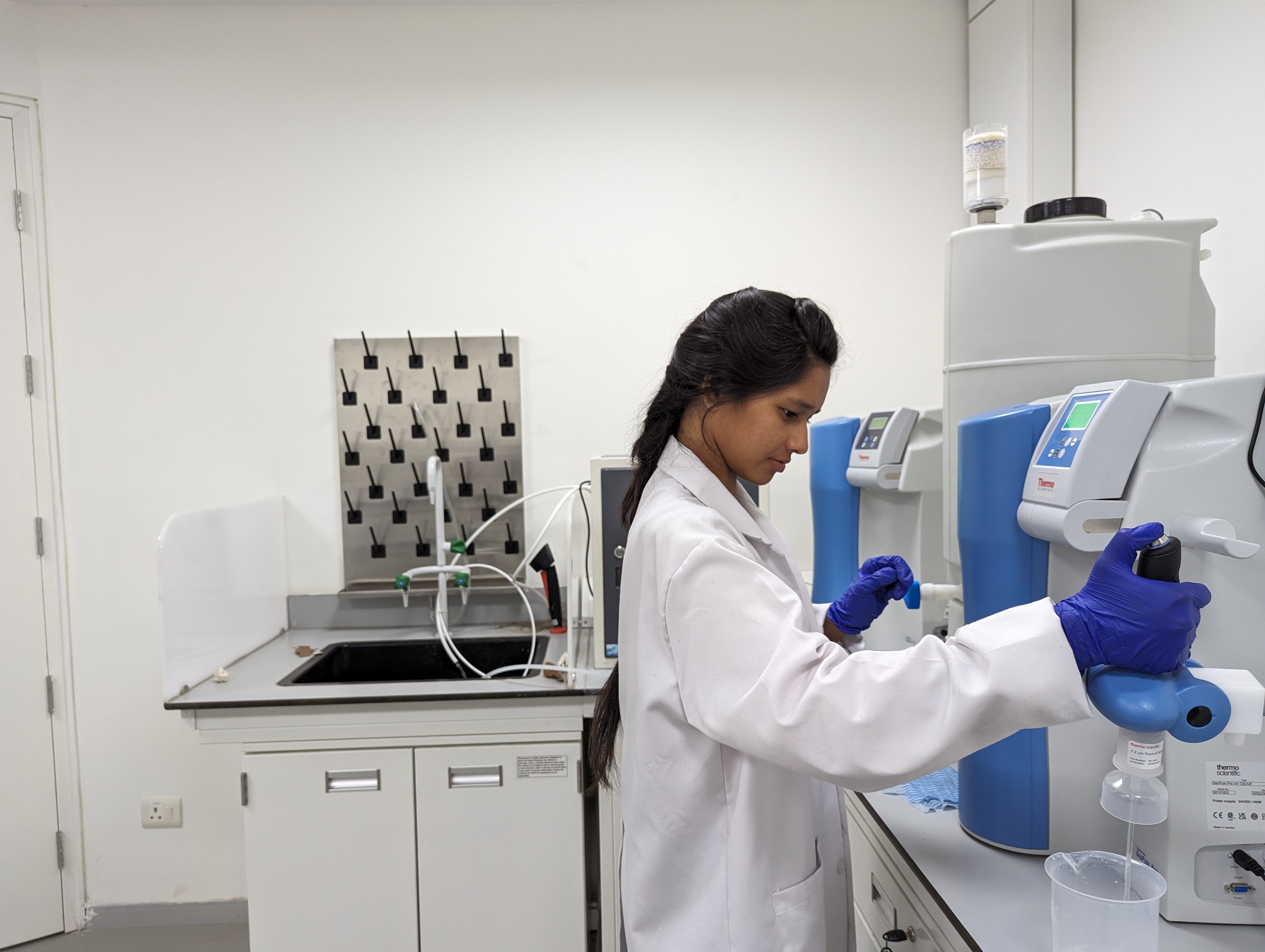

It requires greater re-orientation of our healthcare perceptions as well as vital professional & social networking and participation. Accessing well-curated databases, mobilizing research towards India-specific solutions, and developing precision diagnosis and measurement platforms are our immediate goals.

However, respecting our right to health also means upholding our right to access safe drinking water, clean air, good nutrition, quality housing, decent working conditions, and mental health. While some of these can be tangibly directed into actionable steps, others are less discernible.

Campaigns across the world vouch for improved mental health and wellbeing support to be made available to people as early as possible and at the right level. They also call for access to quality health services, education, and information. But who should be doing this, and who is the beneficiary?

Unless we acknowledge the fact that the issues have more to do with the way we have chosen to live collectively as a human race and allowed technological advances to dictate terms for us, the solutions are going to be temporary and largely eyewash. In the Indian context, it is imperative for every one of us to take out time and analyze the root causes behind the lack of access to safe drinking water, acute air pollution in our cities, deterioration of soil health, and changing climatic conditions that are eventually affecting the nation’s agriculture produce and storage, as well as its mortality rate. In that sense, it is more appropriate for one to say that ‘my health is my responsibility’ .

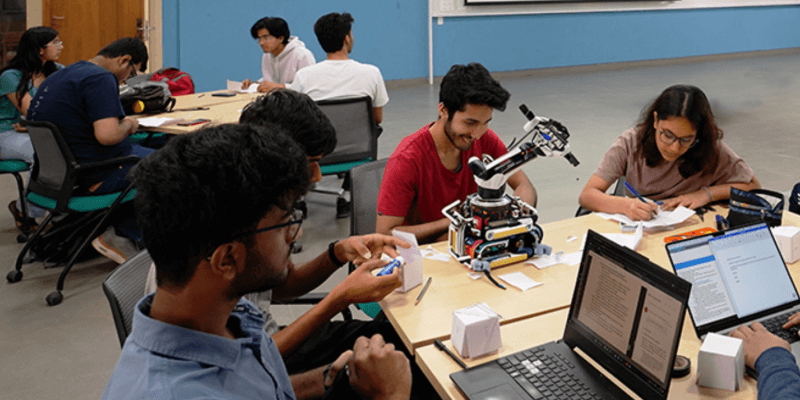

At Plaksha, we, of course, try to address some of the above as part of our mission to reimagine tech education and co-create a world that is inclusive and focused on improving human and planetary health. Teaching young minds and engaging them in projects that deeply ponder on the grand challenges of our time is a pathway to cultivate a young generation that could perhaps change the status quo.

Interdisciplinary research at CEPH also earnestly looks at the elements of air/water pollution and epidemiology that cause different health hazards. Our cutting-edge investigations at the intersection of molecular biology, disease modeling, materials, and next-generation diagnostics would provide a deeper understanding of human physiology in the Indian context and cater to equitable healthcare, particularly for cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Through our research, we aim to gain insights into local health trends, environmental patterns, and social dynamics, and enable evidence-based decision-making to address the root causes of Punjab’s health and associated complex challenges on an early basis .

Dr. Chaitanya Lekshmi Indira (writer) is an associate professor at Plaksha University and serves as the Director of the Center for Equitable and Personalized Health (CEPH).